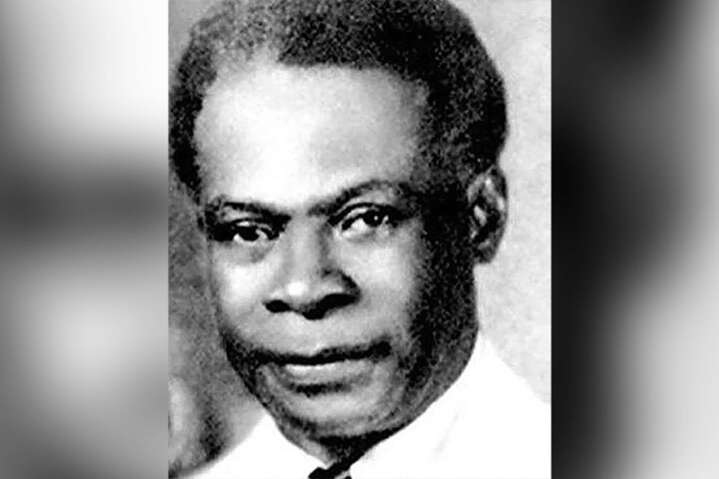

If Leonard Howell were alive, it is likely he would have been one of the stars of today's National Honours and Awards ceremony at King's House. Considered by many the father of Rastafari, he died a forgotten man in 1981.

Howell has been posthumously invested into the Order of Distinction (Officer class), Jamaica's fifth-highest honour. Professor Clinton Hutton of The Mico University College said a national recognition was long overdue.

"I would have preferred the highest national civilian award to be bestowed upon him, [like] the Order of Merit. However, it is still significant that Howell is being recognised in this way," Hutton said.

"Leonard Percival Howell was the principal founder of the Rastafari movement in the early 1930s. Soon he was arrested by the British colonialists for sedition and sentenced to two years in prison. He made the first defence of Rastafari as God and king when he was tried in the Morant Bay Courthouse. And, while serving his prison sentence, he wrote the Promised Key, the first text on Rastafari," Hutton said.

Howell was born in Clarendon in 1897. In 1914 he moved to the United States where he lived for 16 years, serving in the army.

His life is covered in The First Rasta: Leonard Howell And The Rise of Rastafarianism, a 2003 book written by Helene Lee of France. She wrote that during his time in the military Howell travelled extensively and met popular black nationalist leaders of the time, such as his compatriot Marcus Garvey and Trinidadian George Padmore.

Deported from the US in 1932 after serving a two-year prison sentence for grand larceny, Howell first came to public attention in Jamaica when he started selling photographs of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I.

According to Lee, Howell said he would use funds raised from his photos to purchase tickets for a mass return to Africa. His popularity grew to an extent that he became a target of the authorities.

He was sentenced to a two-year prison term in 1933 for sedition and shortly after his release Howell was committed to the asylum.

Howell established his first commune, Tabernacle, in St Thomas, during the late 1930s. But it was at Pinnacle — a 200-hectare expanse in Tredegar Park, St Catherine, bought with money donated by supporters — where he rose to national prominence.

The charismatic leader operated a self-reliant community at Pinnacle for 15 years. Although visitors said Howell and his followers had a thriving farming and basket-weaving commune, others claim that was merely a front for a lucrative ganja export business.

In 1954, Pinnacle was raided by security forces who arrested scores of residents.

Hutton believes awarding Howell an OD is a sign of Jamaica's Government trying to make amends with Rastafarians for decades of injustice prior to Independence in 1962 and in the decade that followed.

"The honouring of Howell is another sign of the Government taking steps to apologise to Rastafari for the evolving generations of injustices meted out to them. The efforts to apologise to and compensate Rastafari for the horrific acts of brutality meted out to them re the so-called Coral Gardens incident eight months after Independence, preceded the honouring of Howell," he noted. "As we struggle for reparation in consequence of European enslavement and native genocide, it is also very important that the Government, as a matter of policy, take full, unambiguous measures at internal reparation. It is within this context that firm consistent steps must be taken to deal with the historical injustices against Rastafari. In this the 60th year of Independence the policy march for justice for Rastafari is but a crawl," Hutton added.

The Coral Gardens stand-off between the police and Rastafarians in that St James community in April 1963 resulted in the deaths of eight people — two policemen, three Rastafarians, and three civilians.

Approximately 143 people received national awards today.